Near real-time: on the edge of OLTP and OLAP. Part 2

In the evolving landscape of global data management, the demand for near-real-time data processing is pushing the boundaries between traditional Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) and Online Analytical Processing (OLAP) systems. In the first part of this series, we established a foundational architecture using Kafka to meet specific customer requirements for data immediacy. Now, we advance the discussion by conducting a detailed comparison of various architectural options and implementation strategies.

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of both batch processing and modern streaming solutions. We will explore how classic batch approaches can be optimized for lower latency and when they remain a cost-effective choice. Subsequently, we will delve into advanced streaming architectures, examining tools like Apache Flink and real-time databases such as Materialize and RisingWave. The objective is to offer practical insights into designing robust systems that balance performance, cost, and complexity, helping data architects worldwide navigate the trade-offs inherent in building effective near-real-time data pipelines.

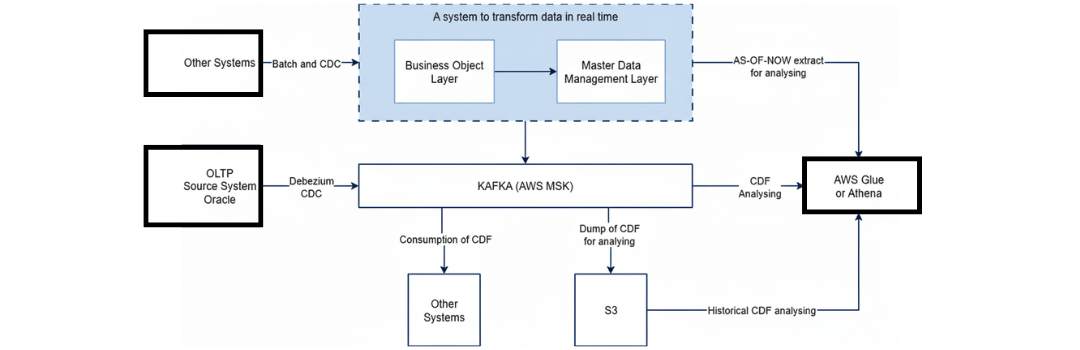

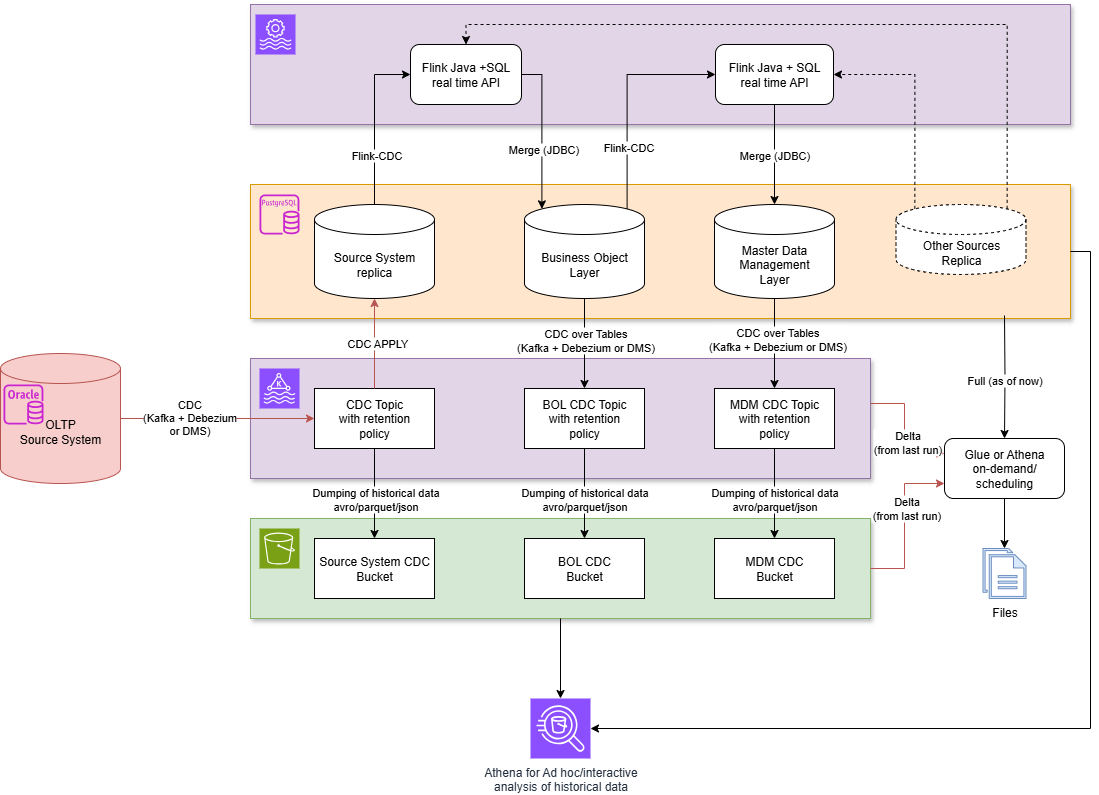

As a reminder, below is what our architecture looked like, please refer to part 1 of this blog post for more information on how we got here:

1. Considered Options for Batch Solutions

Batch processing is the classic pattern for analytical workloads: data is collected, transformed, and written periodically. Typical characteristics and measures in the context of low latency:

- Clocking/interval reduction: The shorter the batch interval (e.g., from hours to minutes or seconds), the closer a batch system comes to near-real-time processing. In practice, however, short intervals are expensive and involve higher operating costs.

- Incremental processing: Instead of complete recalculations, only deltas (changes) are processed (CDC-based or timestamp-based deltas). This reduces workload and latency compared to full runs.

- Materialization & caching: Result tables or materialized views already hold aggregated/merged states, allowing queries to be answered quickly. The frequency of updates determines the effective latency.

- Optimized storage formats: Parquet/ORC, combined with lakehouse formats such as Iceberg/Delta/Hudi, optimize scans, partitioning, and file-level upserts, which speeds up batch runs.

- Architecture trade-offs: Batch reduces complexity and is reproducible but is rarely suitable for sub-60-second latency. For latencies ranging from several tens of seconds to several minutes, well-timed, incremental batch pipelines can be sufficient and cost-effective.

Oracle, Postgres / Aurora — Features, similarities, and differences

Features

- Oracle: Materialized views, in-memory options, mature replication and backup features. Supports automatic refresh mechanisms and offers strong OLTP functionality.

- Postgres / Aurora: Robust open-source RDBMS with replication, WAL-based CDC. Aurora offers managed service features (automatic scaling, snapshots). Postgres requires typical batch scripts or schedulers for recurring materializations.

Identical features

- Both systems can serve as sources for CDC/change feeds (e.g., via Debezium, AWS DMS).

- Both offer SQL interfaces for full and delta exports.

- Both can be used as targets for materialized data models to provide AS-OF-NOW states.

Architecture and implementation differences

- Materialized views: Oracle offers native, automatically triggerable materialized views with various refresh strategies; Postgres does not offer a fully comparable native solution by default (there is REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW, but no continuous automatic refresh at the same level). In Postgres, you often have to use your own schedulers/jobs or triggers.

- Performance optimization: Oracle has proprietary in-memory optimizations; Postgres achieves performance through indexing, partitioning, connection pooling, and the right hardware/instance size (or Aurora specifics).

- Operation & costs: Oracle is generally more license- and operation-intensive; Aurora/Postgres are more cost-efficient and easier to automate in cloud environments.

When to choose which?

- Oracle-like features required: Oracle or an enterprise DB with in-memory and robust materialized views (if budget allows).

- Cost/cloud-first: Postgres/Aurora with incremental batch jobs is often practical – especially if latency of minutes to hours is acceptable.

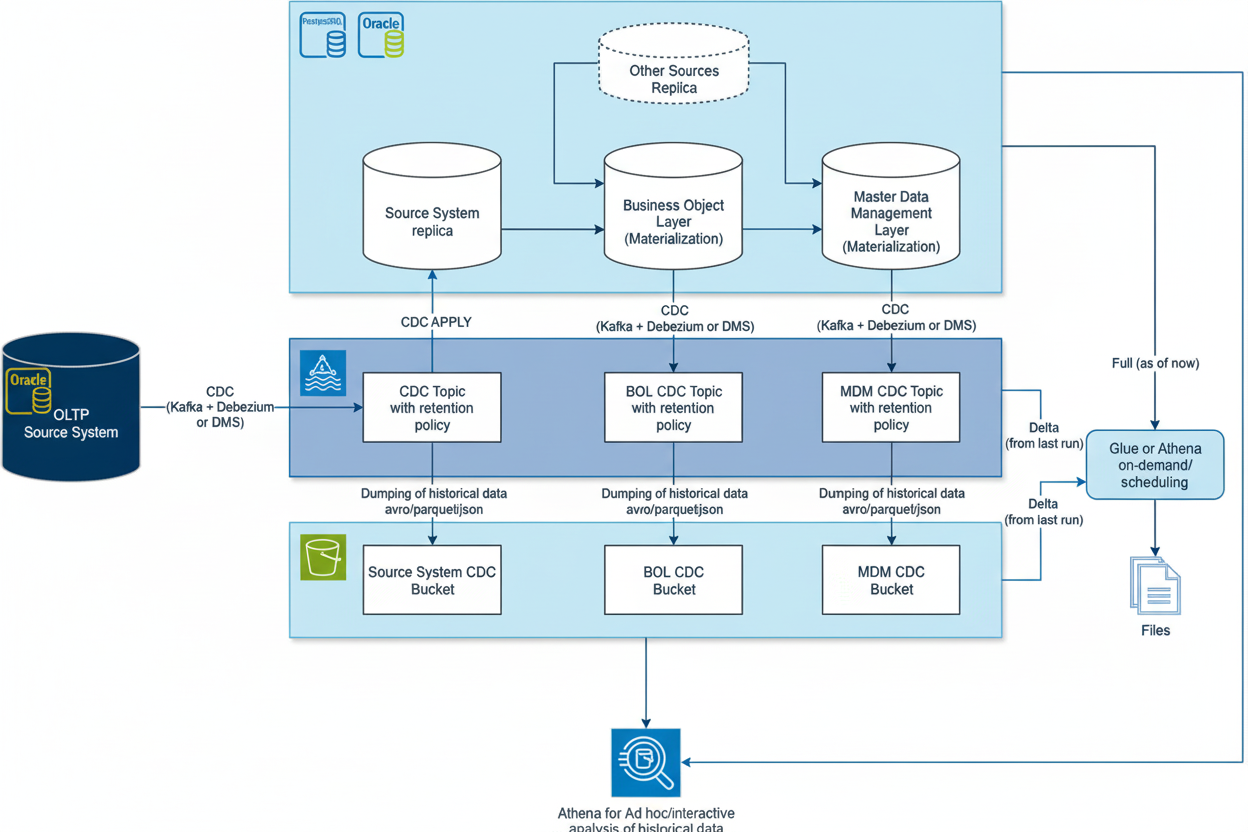

Our architecture for both platforms could look like this:

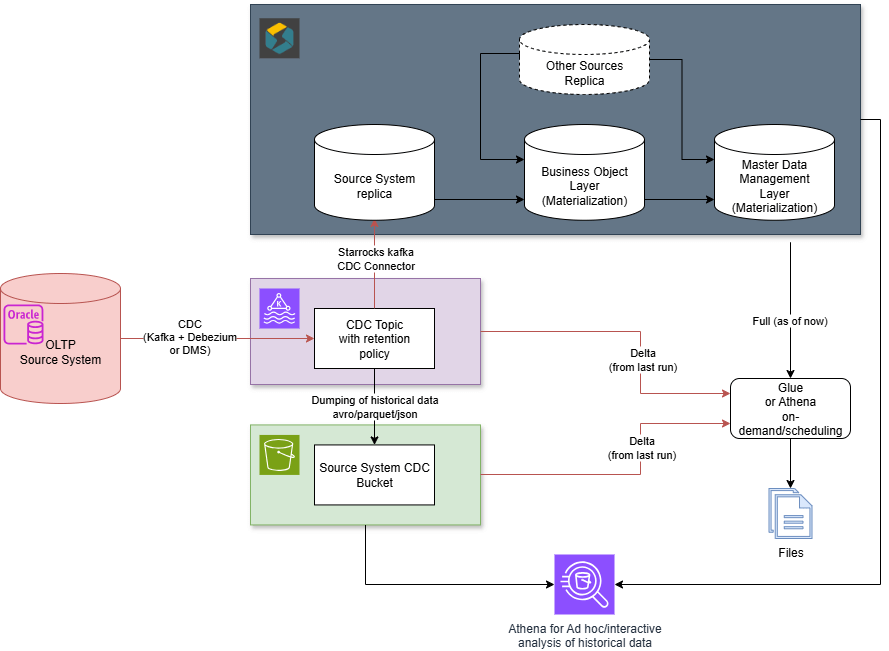

StarRocks — Features, similarities, and differences compared to RDBMS

Features

- In-memory OLAP system with fast analytical queries

- Support for asynchronous materialized views, optimized for analytical workloads

- Good connectivity for ingest (Kafka, batch loads) and high query performance

Similarities with Oracle/Postgres

- Can serve as a target for materializations and provide aggregated view states.

- Supports SQL queries and is optimized for analytical queries.

Differences / Architecture aspects

- Design goal: StarRocks is primarily an analytical engine (OLAP), not a transactional RDBMS. This results in significantly lower read/analytics latencies.

- CDC support: StarRocks does not generate CDC/CDF feeds itself. For complete replication or change tracking from other platforms, a separate CDC path is required (Debezium/DMS → Kafka → StarRocks ingest).

- Materialized view: Materialized views are highly optimized for analytical queries and are easier to use than in Postgres, but less transactionally complete than native RDBMS materialized views.

- Managed service: If a managed offering is desired, providers such as CelerData should be considered.

When to use StarRocks?

- When very fast analytical responses with relatively simple update patterns are required and CDC generation is already performed elsewhere.

- When the goal is to support complex OLAP queries with low latency without the complexity of a full-fledged RDBMS.

- When it is not necessary to generate CDC from StarRocks objects

Our architecture for the StarRocks platform may look like this:

2. Considered Streaming Solutions

Streaming architectures aim to continuously process changes so that systems provide an up-to-date “AS-OF-NOW” state. Key principles:

- End-to-end hop minimization: Each additional intermediate step (source system → Kafka → streaming engine → DB) adds latency. Direct CDC→engine ingest (e.g., Flink CDC) reduces latency compared to an intermediate Kafka hop.

- Stateful stream processing: Engines such as Flink manage local state to perform joins and aggregations efficiently. This enables sub-second to second-level latencies, depending on throughput and complexity.

- Exactly-once / consistency: Latency and consistency are a trade-off. Exactly-once semantics (e.g., via Kafka Transactions or Flink Two-Phase Commit) increase complexity/overhead.

- State materialization: Results often need to be materialized externally (DB, key-value store) or kept as materialized views in specialized systems. Fast, idempotent apply mechanisms are crucial.

- Backfilling & Snapshots: A consistent starting point is necessary when restarting or starting for the first time — often a combination of snapshot + CDC stream (e.g., Debezium snapshot → CDC).

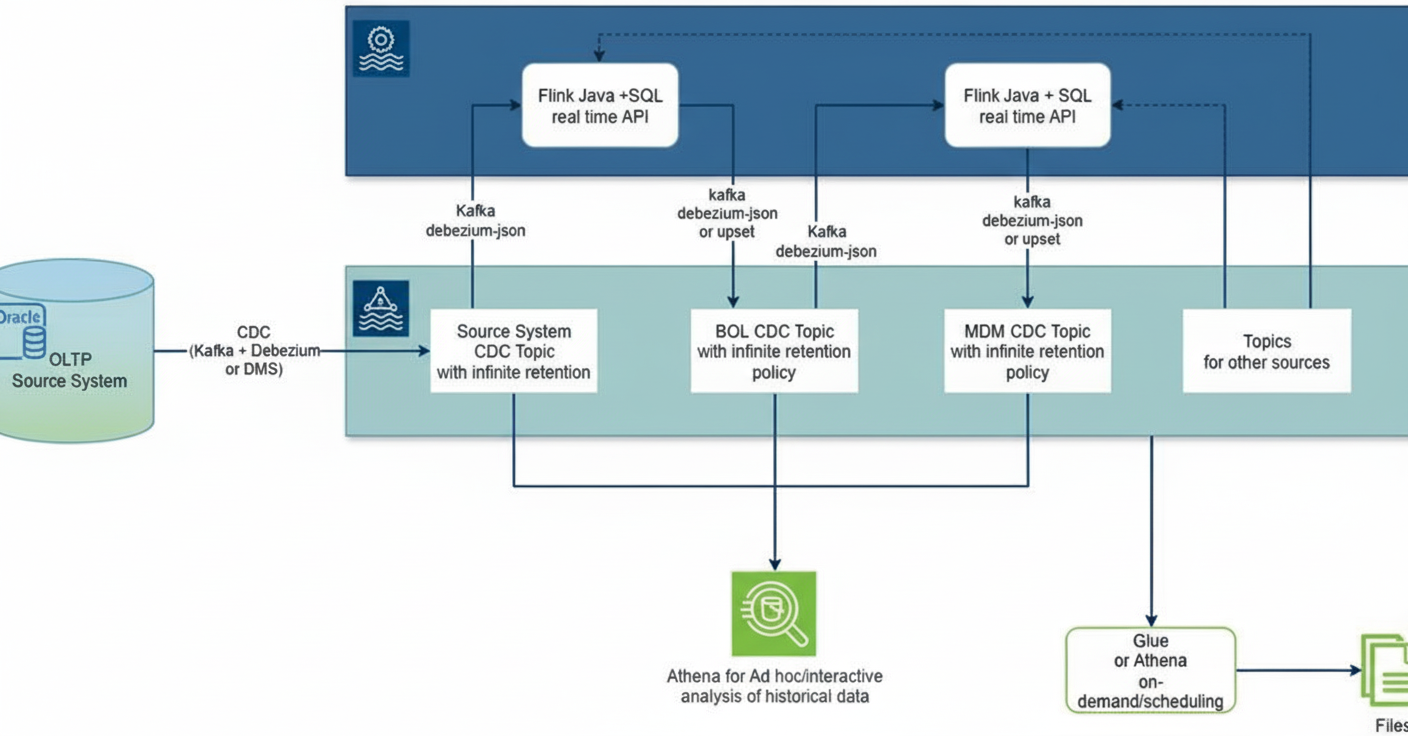

Flink

Flink is a proven engine for stateful stream processing. It scales well, supports exactly-once semantics (in combination with suitable sinks), and can efficiently execute complex joins/windows/state machines. Flink can read CDC directly (via Flink-CDC/Debezium connectors), making Kafka optional.

Flink + Kafka

Architecture: Kafka acts as persistent storage; Flink reads from Kafka, performs joins/aggregations, and writes results back to Kafka.

Advantages

Advantages

- Reading and writing processes are relatively fast

- Flink can read directly from Kafka and write directly to Kafka

- Flink supports automatic detection of Debezium CDC in JSON or AVRO format

Disadvantages

- Event size: JSON must be used as the format because the Flink Kafka connector for AVRO only supports the Confluent Schema Registry (the customer wants to start exclusively with AWS services). JSON requires more storage space on Kafka clusters and is also slower during serialization and deserialization.

- Unnecessary deserialization: Although only certain attributes from the source system tables are required, entire events must always be deserialized when reading from the source system CDC topic – even if only individual fields are subsequently used (e.g., for the path from Oracle → BO layer).

- Different write format: The format used for writing differs from the Debezium Oracle CDC format: Debezium displays update-old and update-new in a single line, while Flink treats them as two separate events when writing to Kafka.

- Historization/audit: For audit purposes and manual analysis, all events must be permanently stored in Kafka. This leads to high storage and operating costs and has a negative impact on performance.

- Join problem: Complete data records are required to join tables correctly. Reading must always start from the oldest offset. Since all events are stored, the amount of data to be processed increases with each restart.

- AS-OF-NOW logic: Since there may be multiple events per key, external tools (e.g., Athena) must determine the latest version for each key and filter out DELETE events if necessary in order to create a valid status (AS-OF-NOW) or, for example, a full extract for dashboards or analyses.

- Selective filtering not possible: If only certain data records are required (e.g., filtered by product), all events must first be extracted from Kafka and then filtered. In Kafka, you can only filter by timestamp or offset—not by content attributes.

- Streaming start & joins: When Flink starts in streaming mode, all sources are started in parallel. In the first few minutes, until all tables are fully loaded into memory, joins do not return any hits, which leads to incorrect results. Solution: Start tables in a defined order – however, this is not trivial in Flink. With regard to Kafka, this can only be controlled via timers (e.g., targeted delay between table loading processes).

Some of these disadvantages can be mitigated by extracting historical data from Kafka and storing it on S3. In addition, topic compaction can be used in Kafka to reduce the volume of data:

Advantages

Advantages

- It is not necessary to permanently store all historical events in Kafka → the Kafka cluster can be smaller

- The analysis of historical data is simplified because tools such as Athena work much more efficiently with S3 files than with Kafka

- Storing data on S3 is cheaper than in Kafka (tiering can also be used)

The disadvantages remain the same as in the previous variant, except, of course, for the analysis of historical data.

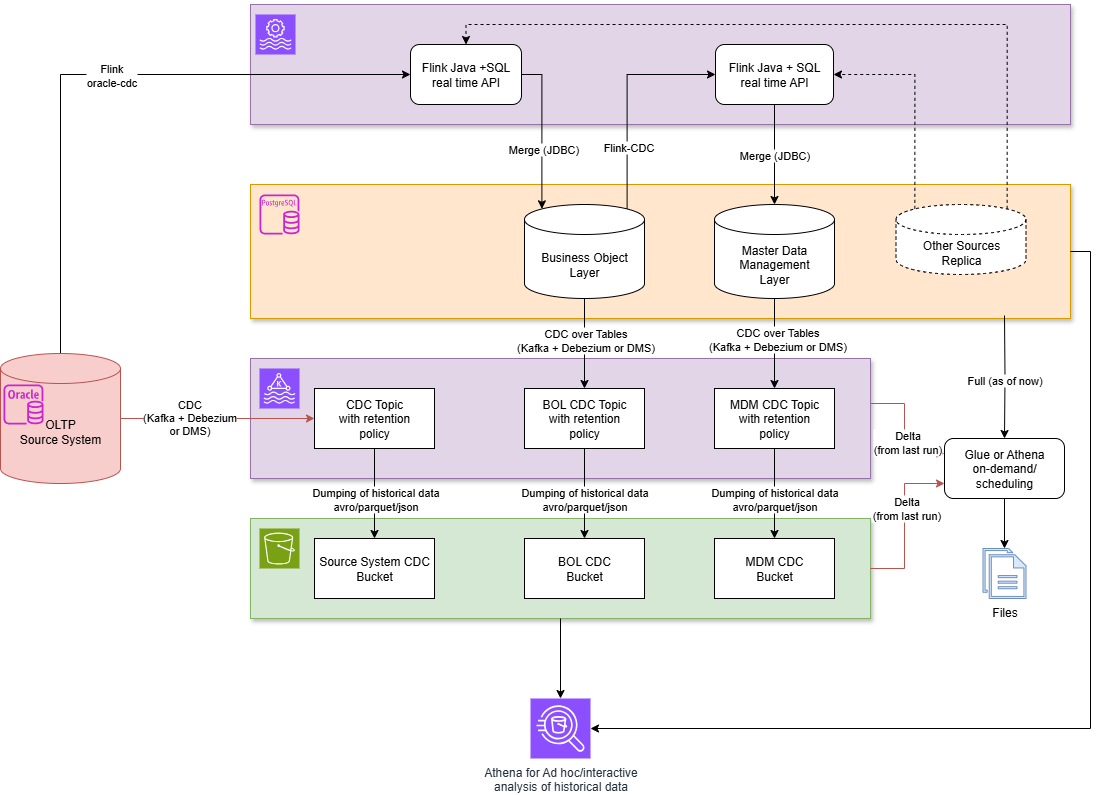

The solution can be further optimized by reading CDC events directly from Oracle – using Flink-CDC instead of Kafka:

Advantages of direct Oracle CDC connection

- Lower latency on the Oracle → BO layer path, because:

- One hop is eliminated

- Only the required fields need to be serialized/deserialized

Disadvantages (remain largely unchanged)

- Event size in the path BO layer → MDM layer remains high: JSON is necessary because Flink’s Kafka connector for AVRO still only supports Confluent Schema Registry. Storage requirements & (de)serialization remain critical

- Flink’s write format still differs from Debezium Oracle CDC format: Updates are written as two separate events

- Complete data records required for joins → Reading from the oldest offset remains necessary; even with topic compaction, more rows are created than with snapshots

- AS-OF-NOW analyses in tools such as Athena still require:

- Creation of the latest version per key

- Exclusion of DELETE events

- Join issues remain when streaming starts: Data sources are started in parallel, which leads to temporarily incorrect join results. The only solution is still to stagger the start times (e.g., with a timer).

Flink + Kafka + Postgres

Architecture: Kafka distributes events; Postgres maintains the AS-OF-NOW state; Flink reads CDC directly from Postgres (thanks to a full replica of the source system) via Debezium, processes data, and materializes results in Postgres.

Advantages

- An AS-OF-NOW state is available at any time in the database with an SQL interface – this helps reduce the load on the source system

- Simple full and delta exports are possible

- Flink can read CDC events directly from Postgres

- Flink supports automatic detection of Debezium CDC for Postgres

- When the process is restarted, a full snapshot is read first, then the CDC stream is transitioned to.

- Historical events do not have to be permanently stored in Kafka → Kafka clusters can be smaller.

- Historical analyses can be performed efficiently via S3 (e.g., via Athena); In addition, full snapshot data from Postgres can be retrieved via JDBC/ODBC with SQL

- Storage on S3 is more cost-effective than in Kafka (tiering is also possible)

Disadvantages

- The latency in the Oracle → BO layer path is higher because several intermediate stations (hops) are involved (see below for possible optimization)

- Writing to Postgres is slower than to Kafka (can be compensated for by larger instance sizes)

- Operating the database causes additional resource requirements and costs

The latency on the Oracle → BO layer path can be reduced if, instead of a complete replica in Postgres, the CDC events are read directly from Oracle:

3. Real-time databases (streaming OLAP)

Real-time databases (streaming OLAP/streaming SQL engines) aim to maintain continuously materialized views that can be queried immediately via SQL. Typical features:

- Continuous materialization: Views are updated incrementally so that queries always see the current state.

- Low technology footprint: Many platforms require fewer complementary components (no separate stream engine + materialize → everything in one system).

- Simple SQL experience: They often offer familiar SQL APIs (JDBC/ODBC), which facilitates ad hoc analysis.

- Latency: Sub-seconds to a few seconds possible, depending on query complexity and resources.

- CDC pipelines: If source systems are not directly supported (e.g., Oracle), a CDC layer (Debezium/AWS DMS → Kafka) is necessary.

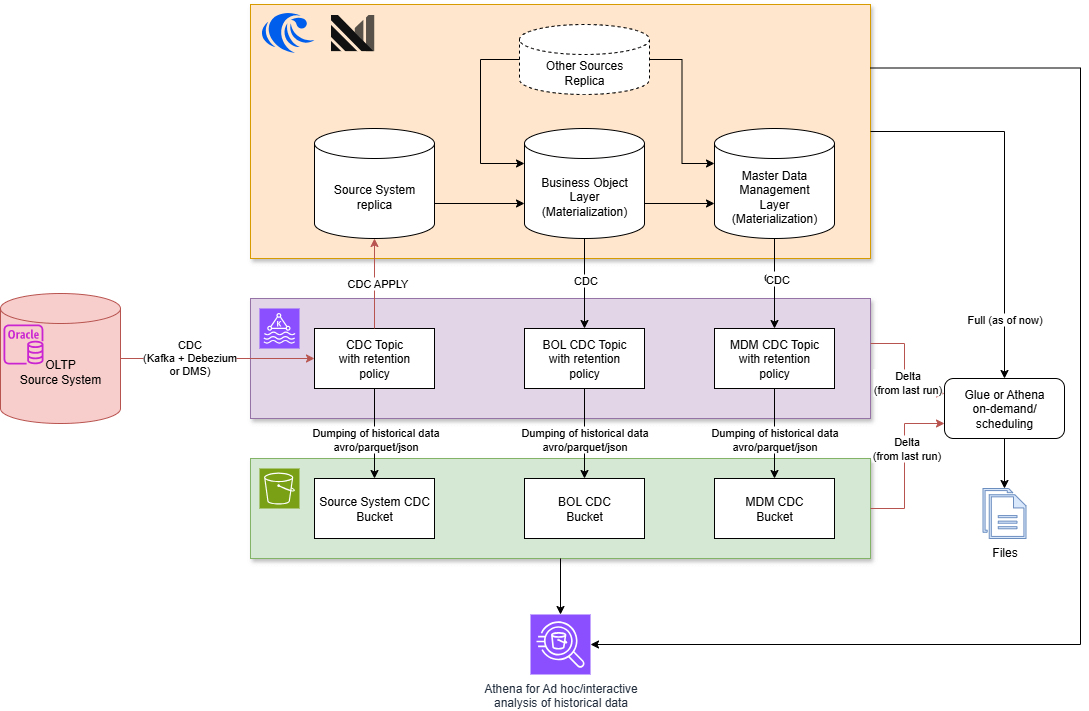

Materialize & RisingWave — Comparison and Context

Key features

- Materialize: Containerized streaming SQL engine designed for fast, incremental materialized views. Supports Kafka ingest, provides SQL access via JDBC/ODBC.

- RisingWave: Similar in concept, with a focus on integration into cloud ecosystems, good performance with large data volumes, and support for persistent materializations.

Architectural differences and similarities

- A replica of the source system is required. This can be seen as both an advantage and a disadvantage: on the one hand, it increases latency and consumes additional storage space; on the other hand, the replica can also be used for read-only processes to reduce the load on the source system.

- Neither platform supports Oracle as a source system, but they can read data from Kafka, which means you need Debezium, AWS DMS, or similar tools to extract CDC from Oracle and store it in Kafka. This can increase latency slightly, as you have additional intermediate stages (hops) (source system -> Kafka -> the platform).

- Compared to Spark or Flink, both platforms have their own data storage systems, so you don’t need additional databases such as Postgres or s3 + lakehouse formats to materialize data. You also don’t need to store data permanently in Kafka, as you always have a full replica.

- Both platforms support the well-known SQL language.

- The architecture is less complicated compared to Spark and Flink solutions, as fewer technologies need to be used.

- Lower learning curve compared to Spark and especially Flink.

- No additional software is required to generate CDC – both platforms support CDC read and write processes from and to Kafka.

- Real-time processing – latency is very low without high hardware requirements. (depending on the complexity of the data processing processes, latency can be in the sub-second range).

- Since both platforms support SQL via JDBC/ODBC, it is easy to extract the AS-OF-NOW state

- The platforms can be used to build real-time dashboards as well as execute real-time ad hoc queries

- You always get stable and consistent results regardless of the number of joined tables and the complexity of the algorithms

As you can see, the architecture is similar to that of Oracle or Postgres as a platform. The difference, however, is that Materialize and RisingWave support real-time data processing.

When are Materialize / RisingWave appropriate?

- Rapid development & simple architecture: When you need an SQL-centric interface, want low complexity, and want to achieve sub-second to second latency.

- AS-OF-NOW analyses: When you need consistently materialized views that can be queried via JDBC/ODBC.

Additional real-time options to consider

- ksqlDB (Kafka Streams SQL): Good if Kafka is the central system; offers streaming SQL close to Kafka and easy integration, but more limited capabilities for complex stateful queries than Flink.

- Apache Pinot / Druid / ClickHouse: These systems are fast analytical stores, good for low-latency dashboards and OLAP, but they typically implement batch/nearline ingest or their own ingestion pipelines (not necessarily incremental materialized views like Materialize).

- SingleStore / Rockset: Commercial systems optimized for very low latency for analytical queries; they often come with their own ingest mechanisms and managed services.

In conclusion, selecting the right architecture for near-real-time data processing requires careful evaluation of the trade-offs between latency, operational complexity, and cost. As we have demonstrated, traditional batch systems can be optimized for lower latency, while modern streaming solutions like Apache Flink, Materialize, and RisingWave offer powerful capabilities for achieving sub-second performance. The optimal choice depends entirely on your specific use case, from the acceptable data freshness for analytics to the technical resources available. By understanding the distinct advantages and implementation challenges of each approach, organizations can design robust, scalable, and cost-effective data pipelines.